One man’s love of music creates lifetime quest for high fidelity.

In November of 2024, I taught a class at the Western Institute of Lifelong Learning (WILL) in Silver City, New Mexico, called How We Heard It: A History of Recorded Sound. Three one-hour sessions covered the phonograph’s invention in 1877, moved from wax cylinders and shellac disks to magnetic tape and vinyl LPs, and concluded with contemporary MP3s. Al’s Audio Museum provided a personalized background for much of the material. Besides just conveying historical facts, the course became a kind of memoir of my formative years as the only son of a true audiophile.

Al Howard Richey (AHR, 1923-2008) was my father. Although a chemical engineer by profession, he loved music remarkably, enough to dedicate countless hours devising better methods for listening. He spent many evenings and weekends building preamps, amplifiers, speaker cabinets, tuners, turntables, and even tone arms. I was there, of course, and this upbringing led me to a career in radio. More about me later . . .

After Al crossed over in May of 2008, our family began to go through his effects. Dad never threw anything away, and his collection of vintage audio equipment told the story of technology’s development from the Victrola era to the compact disk. Instead of junking or selling the devices, I decided to create a museum dedicated to AHR’s legacy.

I consulted with associations in Austin already displaying similar antique collections, but none could spare any space. What ancestral resources could I tap instead? Voila! At scenic Rancho Richey Refuge (RRR), a family property 60 miles south of the Capital City, we had recently restored a ca. 1927 farmhouse. I stashed the first haul of dad’s equipment there, in closet and corner.

The next step in the museum’s evolution happened during the 2008 Thanksgiving holiday. In Corpus Christi to pick up my mom, I searched a broad shelf at the back of the garage for other treasures. Inside cardboard boxes and plastic bags were more and older components. These I lined up on carpet atop the hood of Dad’s Toyota pickup for this photograph.

Just out of frame was a lime-green speaker box that I barely remember. Older sister Betty said it had been her first phonograph and had included an amp chassis inside. Everything else I dusted off and packed into Mom’s Chevrolet Equinox.

While the family gathered at the Rancho, I planned a display for this growing collection of vintage equipment on open shelves. One of the big bedrooms in the farmhouse offered a suitable empty wall. Using lumber salvaged from Al’s childhood home in the Beacon Hill neighborhood of San Antonio, I built a five-foot-tall rack with three levels seven feet wide. My nine-year-old nephew, Aidan Farmayan, helped me with assembly and installation. A photo of the finished array graces the top of this website.

The components line up chronologically, mostly. On the top shelf, in order left to right, are the Knight, Sun, and Bogen amps, Heathkit crossover network, and Heath tape recorder. On the middle shelf are the Williamson preamp and tuner, EICO and Dyna preamps, Sony reel-to-reel tape player, my childhood 78-rpm turntable, and (at first) the Williamson amp and power supply. The bottom shelf is wider to accommodate turntables: Rek-O-Kut three-speed idler, fine-cabinet two-speed, BSR four-speed, and 33-rpm Rek-O-Kut belt-drive. On the cedar chest beneath stands a rougher two-speed turntable.

* * * * *

Al’s Back Pages

AHR’s upbringing in the Alamo City as the second son of a lumberman and housewife didn’t foretell anything overtly technical or musical. His mother, Ella Esther Frick Richey, played a baby-grand piano that she had bought with her own money earned from renting rooms. “Merker,” as we called our grandmother, often performed duets with her sister Francis and neighbor, Mrs. Robinson. Throughout her life, Merker loved attending the San Antonio Symphony concerts, early on with her German-born mom. She could not sit still during performances, conducting the orchestra from her seat.

Father (“Pampaw”) Alfred played “at” the piano somewhat and enjoyed waltzes. My dad’s brother, Elmore, practiced violin as a youth, and an unplayed guitar looked nice atop the piano. The family owned a wind-up record player and table-top radio, through which the family heard such popular favorites as Bob Wills and, perhaps, the NBC Symphony Orchestra broadcasts every Sunday evening beginning in 1937.

Al always claimed he couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket, but he actually did, in a sense. His only instrument ever was a harmonica that he picked up one day and immediately played. He modified it by mounting it sideways inside a tin can, sealing the edges of the hole with wax. This configuration gave the reeds a certain tone, and covering the can’s opening produced a distinctive vibrato.

Dad left home in 1941 to attend Rice University, then called Rice Institute, and study engineering. I recall his telling me about a professor or friend in Houston who introduced him to the joys of classical music. Even then, the orchestral style wasn’t widely popular among average Americans. It was considered “long-haired music,” a term that might have originated from the renowned composer/performer Ignacy Paderewski’s unconventionally lengthy locks. (Lizst, Paganini, and Leopold Stokowski also wore their hair long.) The first record my dad purchased was tenor Lawrence Tibbett doing Largo al Factotum on one side and the Toreador Song on the other. By the time AHR moved to South Texas after college to begin his career at the Celanese Chemical Company around 1946, he was hooked on the classics.

monaural

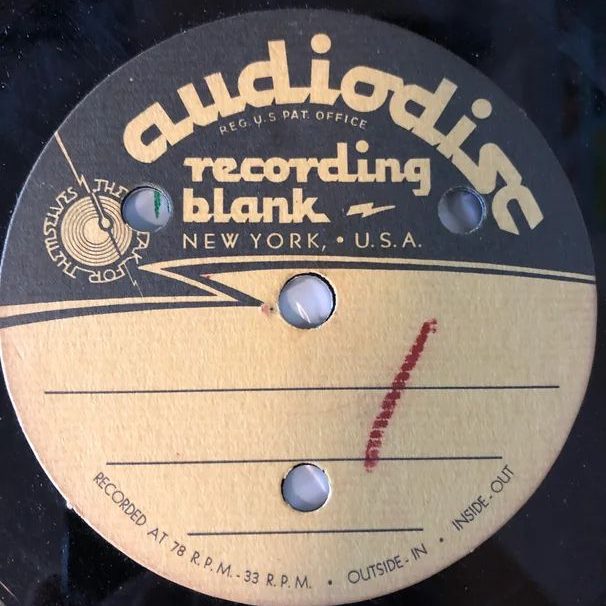

Al Richey met his sweetheart, Hannah Habeeb, at his engineering job in Corpus not long after he moved there, and they married in August of 1947. In June, 1948, Dad’s only sibling, Elmore, brought his disk recorder to the newlyweds. With that contraption, they made a program of make-believe radio interviews. Listen to it here.

tube era

In the middle of 1949, Al and Hannah became the proud parents of a precocious baby girl whom they named Elizabeth and called Betty. Yours truly came along in September of 1952. Besides being a committed and involved breadwinner and eventual father of four children, Al continued to amass audio equipment and recordings—always yearning to better perceive orchestras, vocalists, ballet suites, chamber ensembles, and solo instruments.

Thus, I grew up in a house full of music. The melodies, harmonies, and rhythms I heard from infancy issued from a big single-element speaker in a corner of the living room. Easily 90% of these sounds were symphonic music, since that was my dad’s favorite. I fondly remember melodies of Mozart, Beethoven, and Wagner.

Al built a plywood cabinet in the “old house” on Southland Drive in Corpus. It held both equipment and records. When we moved to the new, Dad-designed home on Dolphin Place in 1957, he made sure the living room coat closet fit the cabinet. This would ostensibly keep the children from messing with the system, but nothing stopped us, of course. Otherwise, however, only the speakers were visible between the other living room furnishings.

binaural

Three things changed after 1957: the family moved to the new house on the south side of the Sparkling City by the Sea; our youngest sister, Carol, was born and became my first roommate; and we rollicked in the brand-new glory of stereophonic sound.

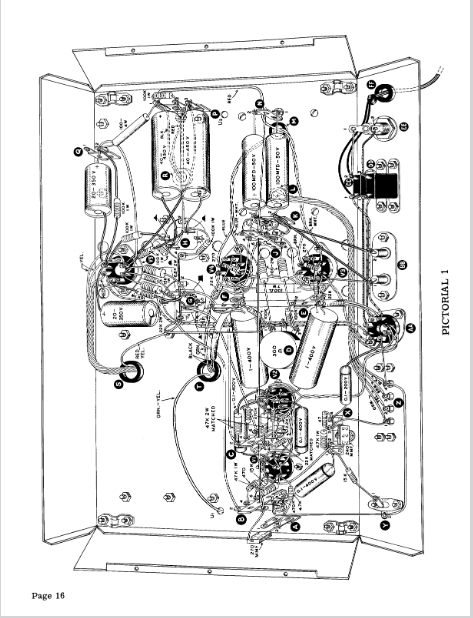

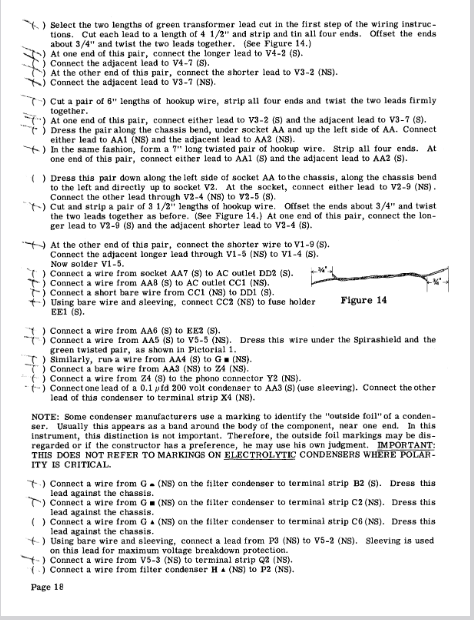

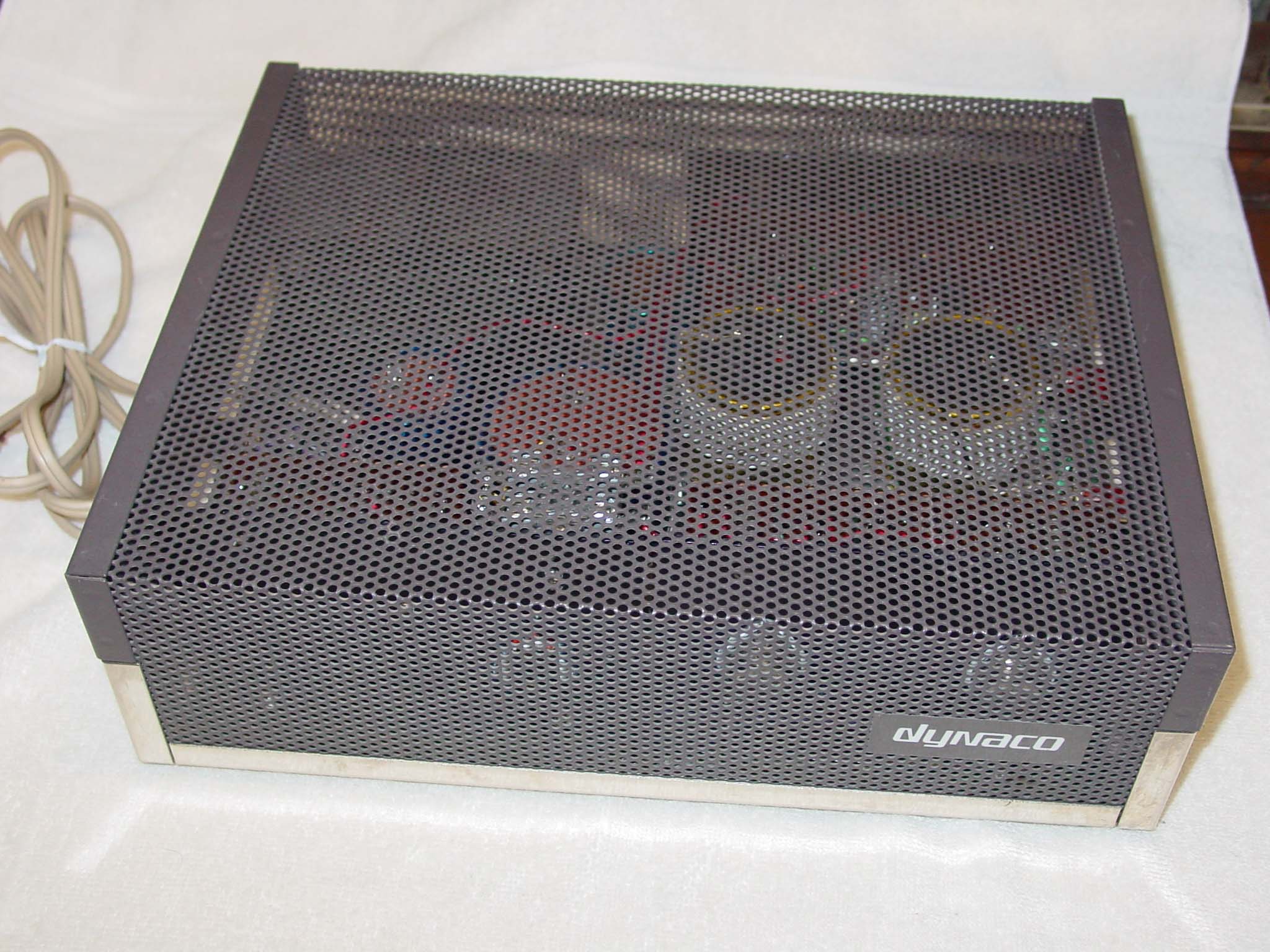

Like other experimenters of the age, Dad at first cobbled together several mismatched components to achieve dual-speaker audio. It should be no surprise that our home boasted the first stereo on the block. Long about 1959, I was helping him build his EICO stereo preamp and Dynakit Stereo 70 amplifier, both kits. The latter gained a major rehabilitation in 2019 and, with its esteemed EL34 matched quads, once again sounds fantastic.

It was in those early days that I first experienced the aroma of rosin-flux solder. Eventually, the Internet might transmit smells, but meantime, I can describe that smoke as darkly sweet, reminiscent of a pine-wood fire. Indeed, it’s made from conifer sap and helps adhesion. Electronic solder itself is an alloy: 60% lead, 40% tin, with a melting point of 374° F. Kit assembly happened on the dining room table with a sheet of plywood protecting it. Dad previously owned some antiquated soldering irons without internal heating elements that needed warming on a stove. I remember his electric one—big and bulky. Only once did I grab the wrong end.

Putting together these contrivances taught us plenty about how they work. All kits came with parts, hardware, wire, and step-by-step assembly instruction manuals.

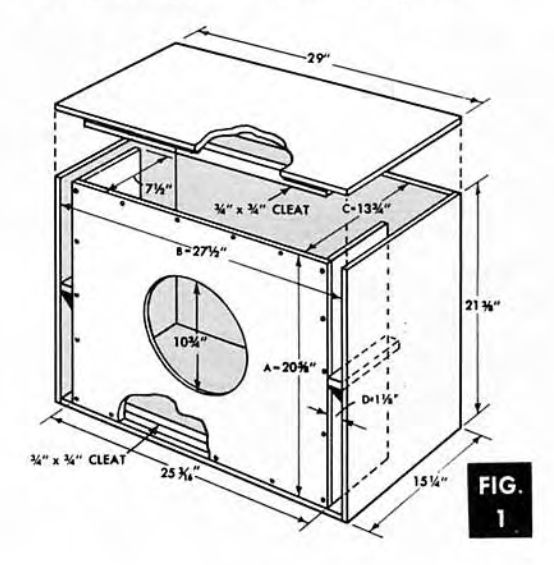

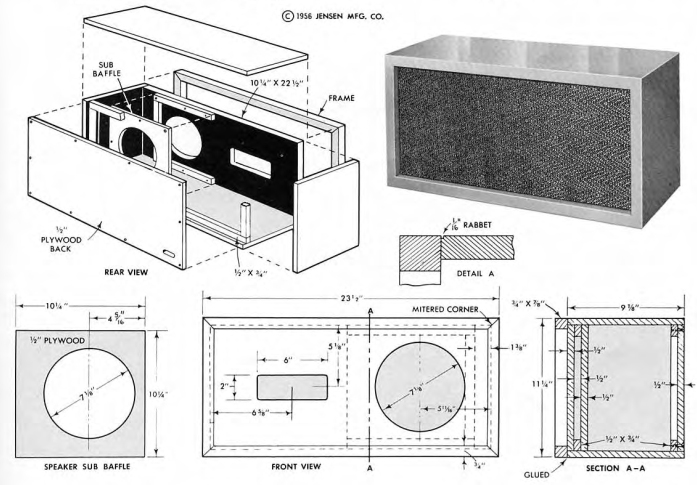

Matching amplification demanded paired reproducers. My Pampaw was a lumberman and carpenter by trade, and his father, E. L. Richey the First, was a genuine cabinetmaker. Consequently, Al also held a reverence for wood, which I inherited. With a design adapted from a Jensen booklet, Dad and I built two bass-reflex, ducted-port speaker cabinets (“Ultraflex”) of 3/4″ plywood.

For woodworking, our theater of operation moved out to the garage for cross-cutting, hammering, drilling, and painting. But always, whether via solder or sawdust, the goal was true reproduction. I’ve retained those same carpentry and electronic skills, and many tools as well, passing them along to my son, Sol.

Top-notch listening was always in the living room. Those big 12” drivers pumped out stereo sound from the EICO preamp and Dynaco ST-70 amp. Often yours truly stood on a hassock and conducted the blaring symphonies. Dad introduced me to all the classics, which I still deeply love. Gradually, especially as big sister Betty became interested in rock ‘n’ roll, Al would reluctantly tolerate other sounds—except for swing or Big Band, which neither of my parents could stomach. Dad wouldn’t admit to liking much pop music, but appreciated their clear resonance as good “test records.” That meant no distortion and fidelity high enough to flaunt the system.

The horn tweeter, constructed to match the mighty Jensen cabinets, featured a built-in crossover network (CN) to protect it from low notes. Dad also built a Heath tube-type CN with wider setting ranges, but still mono. He never got another horn, but I added piezo tweeters (which need no CN) to the cabinets later.

To keep my younger sister, Rosemary, from scratching the grooves, I promoted the safe handling of vinyl with a members-only club—permit required. She eventually got better at it.

“Turn that down!” Mom would cry. Dad replied “But that’s how it’s written!”

Dad’s other priorities were obvious: last house on the street to get air conditioning and color television, but the first with a tape recorder, dating from around 1959. A monophonic Heathkit, it consisted of an upper mechanical section and a lower electronics component, both of which Dad mounted on a rack made of 2x4s and molding. Standing vertically, the drive portion used “keepers,” made from sliced pieces of rubber high-pressure tubing, to attach the reels to their spindles. The electronics consisted of a preamp for the ceramic microphone, record and playback volume potentiometers, input selector, and other controls. The coolest feature was its “magic eye” tube with a blue-green V that monitored recording levels. The recorder sat atop Dad’s slide-front speaker cabinet, which 8” cone was powered by the Bogen amp. This combo stood against the south wall of my bedroom, the one I shared with little sister Carol. The whole family produced some memorable recordings there. In no time, I was making my own tapes of all kinds of juvenile fun, including free-form mock radio programs with sisters and school friends. Here’s one from 1961, digitized for your listening pleasure. The anonymous narrator was my best friend in second grade. I supplied the sound effects, and my late sister Rose delivered a comic Greek chorus in the background.

Al always assured good sound wherever he traveled. The family frequently visited our grandmother and Uncle Elmore in San Antonio. Dad set them up with a progression of record players, usually cast-offs of his own. The Knight amp engages my early memory: it sat in the parlor atop a cabinet with a 15-inch coaxial speaker and curved corners—an artifact, alas, lost to history. To lessen acoustic feedback, the turntable sat in the adjacent dining room. Elmore arranged his record collection geographically, as he did the house decorations: he created Egyptian, Texas, and European rooms.

Since CC had no FM station at first, Dad took his Heath tuner and tape recorder to San Antonio to listen and dub an aircheck, or broadcast excerpt. I remember hearing a trailer for They Came to Cordura, an ad for Saint John’s Bread, and rockin’ Lloyd Price singing Come Into My Heart.

Inspired by a cartoon hero, I designed a basic control panel on cardboard with knobs and switches for play. Seeing me using that, Dad suggested I become a disc jockey—so I did.

* * * * *

Favorite Records

What we heard:

- Peter, Paul and Mary’s first album—enjoyed by all. Dad called them “parts per million.“

- Destination Stereo—first stereo LP we got, its mix quite “ping-pongy,” with nothing in the middle

- History of Boston Symphony and Boston Pops—only 98¢, a great disc from 1956

- Peter and the Wolf—several versions, including Elmore’s, narrated by Eleanor Roosevelt; mine’s by David Bowie

- Young Persons’ Guide to the Orchestra/Carnival of the Animals—spoken by Hugh Downs, verses by Ogden Nash

- “Night on Bald Mountain”—from Fantasia

- Nutcracker Suite—played year-round

- Chet Atkins, My Favorite Guitars—although by a country artist, a bright test record

- Don Giovanni—first complete opera, a box set, also early stereo

- Die Fledermaus—gala presentation with “Anything You Can Do” and “Summertime”

- Marriage of Figaro—second complete opera

- Victor Herbert—“In Old New York” and “Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life” on a couple albums

- Kismet Broadway soundtrack with Alfred Drake, tunes by Alexander Borodin

- 45s, especially Victor Red Seal Classical—RCA’s version of a microgroove at a higher speed. The vinyl was clear crimson. Mom also bought Rosemary Clooney, Vic Damone, and Doris Day. Pro tip: 78 minus 45 equals 33!

- “Rhythm of the Rain”—One of Betty’s earliest singles; she glued “Cascade” from a dishwashing detergent box onto the label.

- Bobby Vee’s Golden Greats—Betty adored this Buddy Holly knock-off.

- Meet the Beatles—Early in 1964, after the Fab Four appeared on Ed Sullivan that memorable time, we procured the introductory Capitol release in mono.

- Beach Boys’ Surfer Girl—Before the British Invasion, those sand/sea bums held supreme.

Where we shopped: Kelly’s Music Store situated in the same shopping center as Uncle William’s Buxtons Jewelers, a place to which I could hike or bike. Operated by Gene [forgot], whose name wasn’t Kelly, the store sold LPs and 45s plus styli and other basics. I think the man may have cut me some deals because he knew Dad and I called him by name. He had an enormous listening room in his house, which Dad once visited. An entire wall of speakers was disguised behind a curtain. Other places to buy records included Woolco with its 99¢ bargain-basement singles and Sol Green’s music store over on Alameda near Ray High School.

KEYS was the local top-40 station, 1440 Khz on our dial, with studios downtown behind a picture window. Betty loved DJ Johnny Marks.

solid state

Time and technology continued its relentless march. Vacuum tubes deferred to transistors, and bass-reflex made way for acoustic suspension loudspeakers. Dad bought and built two Dynakits: PAT 4 and ST 120, then purchased a pair of KLH 6s.

We no longer had to wait for the amp to “warm up,” and the closet stayed cool. There were some of his first store-bought speakers, but Dad always insisted that they feature genuine wood veneer.

Cassette decks came and went, but nary a four- or eight-track ever.

Spacial stereo—From a magazine article, Dad and I learned how to hook up a third speaker from the two hot terminals of both channels on the back of the amp. That produced the difference between the speakers, as opposed to the sum. It gave an echo or ambience to the rear of the listening room. Brian Eno recommended the technique on one of his album covers. I employ this tactic even today, everywhere.

I left home in September of 1971 to attend The University of Texas at Austin and study radio-TV-film. My dorm sound system consisted of a Heathkit Compact Stereo Center unit with roll-top cover, turntable, tuner, and auxiliary input. I built two smaller Jensen-design cabinets (“Treasure Chest”) with 8″ drivers and piezo tweeters for listening.

After I fled the nest, Dad continued to tweak his system, adding regular good-quality receivers and a compact disc player. The rest of my story, including a broadcasting career, awaits telling in another chapter.

* * * * *

The Museum Today

The following image shows a more recent aspect, replete with ancestral photographs.

There’s more: in a nearby room sits a horn tweeter which matches the Bass Ultraflex-12 Jensen speakers and my second Heathkit, a three-tube, regenerative-circuit shortwave radio.

The museum’s contents have changed a bit over the years, but not its mission of keeping Al Richey’s work and memory alive.

There you have it! Please share your similar memories in the comments section. Until then . . .

Good Sound to You!